Deep in the underground of KITATUS and Friends HQ, work has been progressing along on coreUPTED - an exciting action-shooter that bases itself in the world of retro aesthetics whilst drowning that vibe in modern rendering techniques. Think PS1-style 3D models, 128x128 nearest-neighbour scaled textures with fully ray-traced lighting and full physically-based rendering.

The world of coreUPTED takes place inside the cyberspace, the hollywood interpretation of the internet.

To pay homage to some of the more quirkier versions of cyberspace, especially during the concept phase of coreUPTED, there was much deliberation on how it looks. You could go with an unlit shader model to make it feel like a retro game, you could go with a pure wireframe aesthetic or you could go all out and do a mish-mash of retro and modern rendering techniques to create something that sticks out amongst all the retro-styled games around these days.

As you can probably surmise, the mish-mash option won out as the default option for coreUpted but this posed a handful of problems for the project as a whole:

- Raytracing is pretty expensive and locks a lot of less powerful machines out of the experience.

- Wireframes and unlit still looked cool and for some people, they might still prefer that aesthetic.

- There’s debate online on features such as bloom and motion blur, some people REALLY dislike them but if they turned it off whilst keeping the rest of the features on, the creative vision of coreUPTED would be compromised.

Naturally, the solution would be to support the other view modes (Unlit and Wireframe) in addition to the performance-expensive “super pretty” view mode. The problem was getting this to work in Unreal was quite a struggle.

The Problem

For those who have experience with Unreal Engine 4 / 5, you might know that you can toggle different view modes by pressing the F1, F2, F3 .etc keys whilst playing in editor (or in a Development build). This was a great first step as it gave us an immediate representation of what our three different view modes could look like. However, there were still some cons as well as a massive big one that almost made the whole idea of multiple view modes impossible to implement.

One of the more annoying cons were the fact that the debug view modes disabled all post-processing - which meant the image we got was the final image, we could not make any tweaks or adjustments to create the aesthetic we wanted with the alternative view modes.

The major “uh-oh, maybe this won’t work” moment came with the revelation that even via console commands, these view modes are stripped out of stripping builds. As you can probably guess, this was a major “uh-oh” which essentially rendered the original intent of multiple view modes completely impossible from the word go.

The Solutions That Didn’t Work

The first port of call when something isn’t working is to hit up Google; looking up threads on the Unreal Engine forums, Reddit posts and (if you’re lucky enough to have access) UDN.

From looking at countless websites, posts and discussions - having view modes stripped in shipping builds is definitely something people have attempted before with varying levels of success.

The method that consistently came up from this web-hunting was to add

r.ForceDebugViewModes=1

into either ConsoleVariables.ini or DefaultEngine.ini under the RendererSettings section. Some had also recommended adding:

r.ShaderComplexity.CacheShaders=true

Unfortunately, after a handful of builds and tweaks, these didn’t solve the problem - the view modes were still being stripped out of shipping builds. For those wondering, this means both the F1, F2, F3 and the console commands to force enable them.

Frustratingly, it was back to the drawing board.

After many hours of searching the internet later, the consensus was “If that didn’t work, you need to make X, Y, Z changes to the engine to brute-force it on”. After going down that rabbit hole, I can save you the trouble - the engine still strips these view modes out due to reliance on some editor functionality to work.

This was the first hint that things have probably changed since earlier Unreal Engine versions and this approach simply wasn’t going to work.

After this, there were many hours of tweaking the GameViewport class to try and trick it on but eventually, it was clear, that the engine simply won’t allow you to enable these view modes in shipping builds.

Perhaps it was time to throw in the towel or perhaps, it was time to deploy an unorthodox solution to get the functionality we required. Enough fooling around with reading posts and forums, it was time to take this problem into our own hands.

The Plan For The Solution That Eventually Worked

The plan we eventually deployed was (and still is) very tedious but it WORKS.

There are two main rendered objects within a scene in Unreal (unless you count BSPs, but we don’t use them in our project); Static Meshes and Skeletal Meshes.

Of these two main rendered object types, they can be one of two things; Actors or Components. To help illustrate this, a static mesh placed in a scene is a StaticMeshActor but a Blueprint with a Static Mesh inside uses a StaticMeshComponent.

The general idea would be to override what these four types of objects were doing instead of trying to hack open the engine or providing a post-process solution that only made the final image look kind of correct.

At this point, you might be thinking “Why not just stick all this in one material and change the parameter at runtime?”. Annoyingly to add another pain point to this process, wireframe materials - Actual wireframes and not fake ones using Triplanar mapping (which would look terrible on anything that moves!) ARE available in Unreal Engine but your material has to have a check-mark enabled before compilation to turn the feature on - you can’t toggle it at runtime.

So we have four different objects and a library of materials, where to go from here? But somehow we needed to be able to tell them “Hey the view mode has been updated, change out your materials”.

Step 1 - The Component

The first step in this three-step plan is to create a component, more specifically CU_MasterMaterial. This class is an ActorComponent that can be slotted pretty much anywhere. This component stores the materials used when a “View Mode” is switched (Default, Unlit and Wireframe). It does this with three Arrays. In the future, this will probably be refactored into a:

TMap<EViewMode, UMaterialInterface*>

For now, three arrays work fine from the proof-of-concept, so there’s no urgent requirement for a refactor on coreUPTED - at least at the moment.

This class has a handful of things that are super helpful for the use case:

- Dynamic Multicast Delegate - ViewModeUpdated: Triggered when a ViewMode is updated, used for Actors / Components that need to do something special when the view mode has been updated.

- Material Arrays - The Materials the class this is attached to should use

- Function - ForceUpdateMaterial: The function triggered from outside to begin the material update.

The .cpp is another place that could be refactored down the line but functionally it’s fine at the moment. The .cpp simply holds the ForceUpdateMaterial function that checks the ViewMode and broadcasts ViewModeUpdate accordingly. In the future, the if statements will be replaced with a switch case scenario.

Step 2 - The Children

Next, we move to the “Children”, which are three classes in particular:

- UCU_SkeletalMeshComponent

- ACU_StaticMeshActor

- UCU_StaticMeshActorComp

Those keened-eyed amongst you could see that a “CU_SkeletalMeshActor” is missing. That is only since we don’t have any standalone SkeleltalMeshActors in coreUPTED.

The general make-up of each of these classes is that they at children classes of:

- UCU_SkeletalMeshComponent - USkeletalMeshComponent

- ACU_StaticMeshActor - AStaticMeshActor

- UCU_StaticMeshActorComp - UStaticMeshComponent

All these classes have:

- Constructor - This is where we CreateDefaultSubObject for the UCU_MasterMaterial Component

- PostEditChangeProperty / OnConstruction - Depending on if it’s a component/actor, used for filling in default material from the array

- MaterialComp - Reference to the attached UCU_MasterMaterial Component

- BeginPlay - Used for assigning the ViewMode delegate from the MaterialComp

- Function: UpdateMaterials - Is Triggered when the UCU_MasterMaterial Delegate broadcasts out to set the correct material

Now, in the scene, we can replace all the existing StaticMesh Actors/components in the scene / our blueprints with these children classes and they’ll have access to the UCU_MasterMaterial that is technically “built into” the classes.

Step 3 - The Trigger

Now that the classes we require have their UCU_MasterMaterial’s attached, attention now needs to turn to how to get all of these classes to trigger UpdateMaterials (and with the correct value).

We can really do this anywhere but it was decided in this case to stick it in a Blueprint Function Library so that it can be triggered from literally anywhere.

Note: By the time that we got to this part of the code base UpdateMaterials was remade to ForceUpdateMaterial just for clarity’s sake.

This is not the most ideal solution (spoilers: you’ll see the right steps towards on later on in this devlog) but when triggered, ForceViewMode cycles through all the actors in the scene and and checks if they have a UCU_MasterMaterial component. If they do, they’ll set the new material based upon the correct view mode.

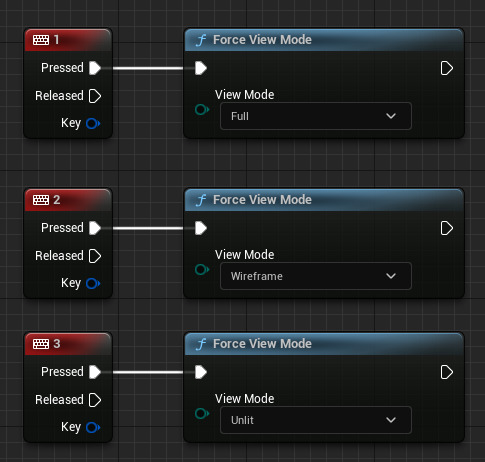

This can then be triggered anywhere; in the case of coreUPTED - for debug purposes, it was placed on the keys “1”, “2”, “3” on the Character Blueprint - where 1 is “Full”, “2” is Wireframe and “3” is Unlit.

A screenshot of the Character Blueprint.

A screenshot of the Character Blueprint.

Step 4 - Those Left Behind

In theory now would just be the case of going through the meshes and updating their material values and calling it a day. However, things don’t like to be that simple. Whilst most classes would correctly update thanks to the loop in the Blueprint Function Library - certain classes decided for one reason or another to exclude themselves from the loop - meaning they weren’t getting updated.

In the case of coreUPTED, we ended up with a “hacky” solution that turned out to be more performant that original looping method in the Function Library (although at the moment both methods exist within the project awaiting a slight refactor).

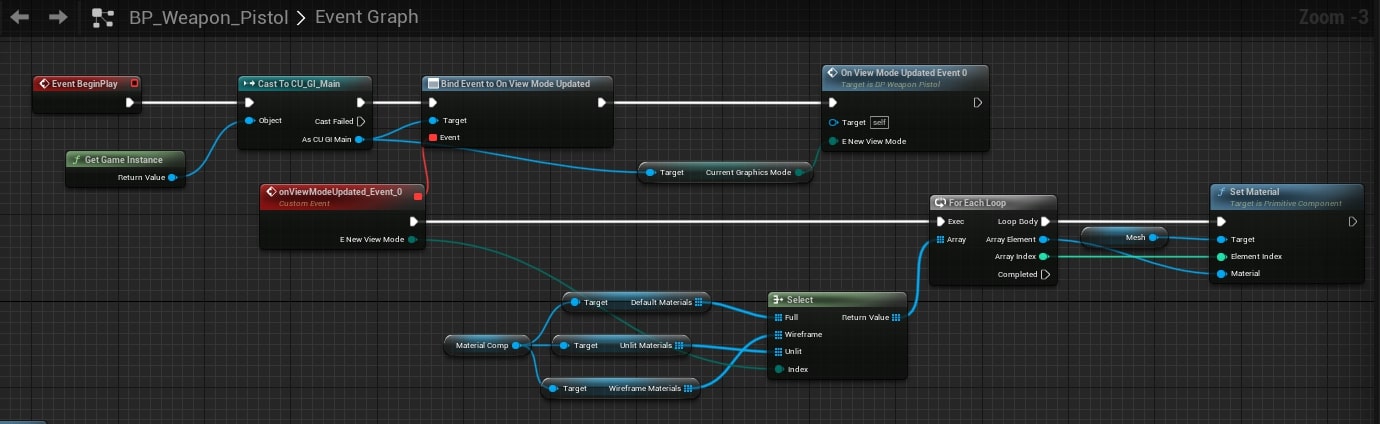

The idea for those “left behind” meshes that aren’t being collected during the loop was to have them subscribe to the GameInstance (or more specifically a delegate on the game instance) that gets broadcasted when the function library throws its loop.

The general flow is: Object created > Begin Play > (Get GameInstance)->Assign ViewmodeUpdated.

The ViewModeUpdated function would then simply trigger the “ForceUpdateMaterials” function on the MasterMaterial component and all was well again.

An example of the “Subscription” method.

An example of the “Subscription” method.

During the next refactor, we’ll remove the loop completely and only keep the code that has the objects that need to update their materials subscribe to the GameInstance.

Step ??? - Bonus Round - Editor Utility

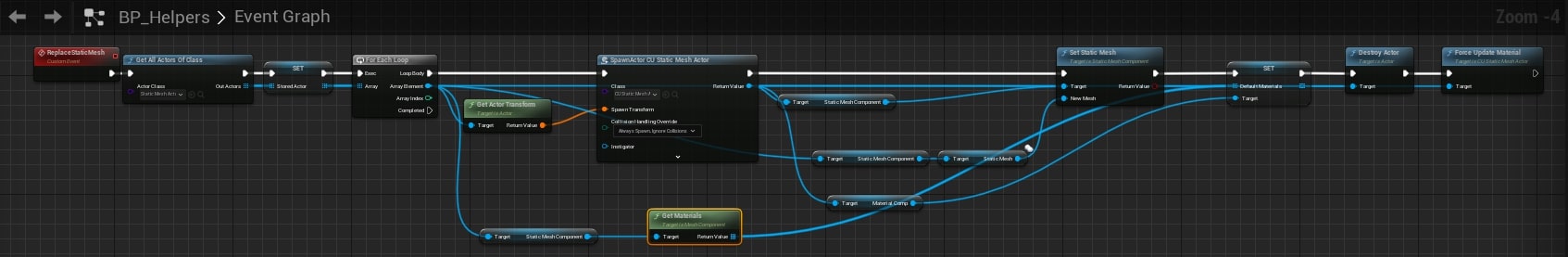

As a little bonus, we had already built a test level with meshes before coming up with this system. Going in and changing every mesh in the scene would be very tedious. Instead, we created an Actor Blueprint with a “Call In Editor” function that allows you to create blueprint functionality to trigger within the editor itself. You would place the Actor within the scene and then trigger the event.

The function got all of the static mesh actors in the scene and then created a ACU_StaticMeshActor actor. It copied over the mesh, transform and materials of the original actor and placed them onto the ACU_StaticMeshActor. Once that was all done, it would delete the original static mesh - leaving us with a scene that looked identical to before but had all of our actors setup correctly for the View Mode system to work.

A look at the call in editor function in our actor class BP_Helpers.

A look at the call in editor function in our actor class BP_Helpers.